Mimmo Paladino’s “Sand Horse”

Located in the space between the temples of Hera and Neptune, in the southern sanctuary of Paestum, Mimmo Paladino’s “Sand Horse”, an approximately 4-metre-high, sand-covered sculpture, may seem an “out of place” intrusion in an archaeological site. But the sculpture, displayed here since 11 July 2019 thanks to an agreement stipulated between the Paestum Archaeological Park and the Museum of Minimal Contemporary Art Materials (MMMAC), actually offers many starting points to reflect on architecture, on rituality and ancient mythology and on how all that is relevant today. Paladino’s horse, made in 1999, was created with sand from Paestum’s beaches. Before it became Paestum, the city was called Poseidonia, from Poseidon, the sea god. But Poseidon is also the lord of horses.

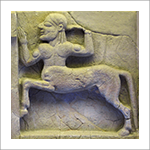

He is the father of the winged horse Pegasus, birthed by the fearsome Medusa. As remarked by Erika Simon, Poseidon’s horses are not necessarily tamed, but are originally as wild and powerful as the mythical Pegasus (Die Götter der Griechen [The Greeks’ Gods], Hirmer, 1969, pp. 70-71).

They therefore symbolise a natural and primeval force, but also the use that man can make of it. The same ambiguity characterises the relationship between Poseidon and the sea. The sea is a source of wealth, but also a deadly danger, as Ulysses knows well, as he was persecuted by the sea god for ten years before going back to his Ithaca.

They therefore symbolise a natural and primeval force, but also the use that man can make of it. The same ambiguity characterises the relationship between Poseidon and the sea. The sea is a source of wealth, but also a deadly danger, as Ulysses knows well, as he was persecuted by the sea god for ten years before going back to his Ithaca.

Therefore, Poseidon represents the ambiguity of the natural forces, between threat and advantage, between calamity and exploitation. And this leads us back to the history of Poseidonia; indeed, it opens up a new outlook on a possible explanation of the city’s name. Why is Paestum originally the city of Poseidon?

Perhaps because, from its very foundation, its inhabitants, who had arrived by sea, fought against water: we must picture the fact that when the Greek colonists arrived in these lands, around 600 BC, the site of the future city of Poseidonia was surrounded by marshes, waterways (the Capodifiume river still flows along the ancient walls), lagoons.

The sea was closer. What is more, the site was at high seismic risk – not only does water flow, but even the earth moves! And who moves it is none other than the “earth shaker”, as Poseidon was called already by Homer.

The sea was closer. What is more, the site was at high seismic risk – not only does water flow, but even the earth moves! And who moves it is none other than the “earth shaker”, as Poseidon was called already by Homer.

Against this fluid and humid environment, the Greeks erected extremely solid buildings: the temples, but also the casket tombs, made of large travertine slabs, such as the one of the Diver.

Recent excavations showed that even the private residences of Poseidon’s colony could achieve remarkable grandiosity. The history of Poseidonia unfolds against the background of the dual nature of the god that the city was named after: the water, the sea were perceived as a resource and as the basis of Mediterranean connectivity, but also as a continuous threat.

And the horse might be the wild one, similar to the angered centaurs that we see fighting against Heracles on the metopes from the sanctuary of Hera on the mouth of the Sele, but also the tamed one on which the knights of Poseidonia went to war and whose effigies were set up in the sanctuaries of the city – more or less in the same place where Paladino’s sculpture was placed.

And the horse might be the wild one, similar to the angered centaurs that we see fighting against Heracles on the metopes from the sanctuary of Hera on the mouth of the Sele, but also the tamed one on which the knights of Poseidonia went to war and whose effigies were set up in the sanctuaries of the city – more or less in the same place where Paladino’s sculpture was placed.